Buyer safety through the lens of the 4Qs Marcus Cauchi podcast

>

Buyer safety through the lens of the 4Qs 🎙️ Marcus Cauchi podcast

I caught up with the Chief Revenue Officer from White Rabbit, Marcus Cauchi, on his acclaimed podcast show, The Inquisitor. Marcus explores how the 4Qs helps business leaders overcome friction and reinforce buyer safety.

run_frictionless are supporters of Marcus’s buyer safety model. If you’d like to understand how to deliver buyer safety to your customers, tune into this cast of The Inquisitor.

Now, on with the show!

MARCUS’S SPIEL

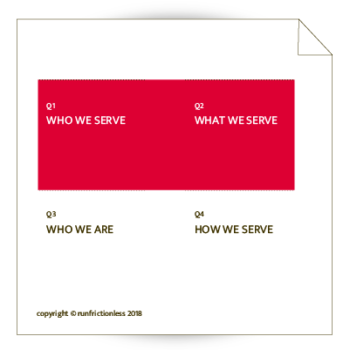

Anthony Coundouris, author of #RunFrictionless, and I explore his excellent perspectives on how to evaluate and understand your customer? Where are you and your business in relation to where your customer is? We delve into the interplay between the various moving parts?

We identify why you can get so much more done when you focus on eliminating the causes of friction for the customer, for the people in your own organization. And how the payoff is a strong, organic business where you are no longer affecting the day-to-day smooth running of your operation. You have the right people in place and you trust them to do the right thing. That is an achievement few ever attain.

q. Who do we serve today?

We will not be everything to everyone.

A common phrase I hear technical founders tell me is “anyone can buy the product.” While that is true, it is not anyone you are trying to convince to buy. You’re trying to convince one person, Sally, to buy, and Sally won’t buy if Sally is not convinced the product is right for her.

q. Are we thinking about who we serve tomorrow?

There may be customer profiles that you are not economically able to serve today. However, you forecast they are likely to fit the 4Qs in the next 12–24 months because of changing circumstances in your company or in the market.

Perhaps their volume of consumption is too small to make a relationship with this profile profitable. They are casual rather than heavy users. Perhaps the cost of acquiring them puts this profile out of reach. Or maybe the profile requires customization of Quadrant 2 before the product provides enough utility.

Either way, this profile could derive some utility from your product. However, rather than invite them into the business today and risk jeopardizing the relationship, you put this customer on a waiting list and serve them tomorrow. Here’s how this dialogue could play out.

Founder: OK. So I could sell you what we have today, but I know you won’t like it. It will fall short of your expectations.

Sally: Oh dear, we really wanted to use your product today.

Founder: You will be the first to know as soon as we have the next release of the software live.

Sally: Thanks for being honest.

Founder: Give me your name, your number, and email address and I’ll call you tomorrow when we are ready to serve you.

q. Are you blocking customers you don't serve?

If in doubt about whether to serve a customer profile, ask yourself this question. If you know in your heart a customer will not write a positive review 👍 after you perform a service, this profile may be better served tomorrow or not at all. Spend your day serving customers who need you right now, and cut waste expended serving folk who will never become a customer.

Why didn’t you tell me that from the beginning. You pretended I was a customer by serving me when in fact you were never going to serve me.

q. Are you name limitations in Q2?

Buyer confidence – smart buyers know there is no such thing as a product that does everything.

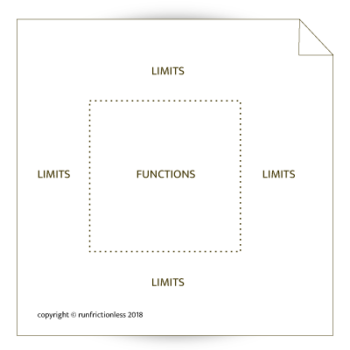

The product fact sheet also needs to inform the customer of known limitations. In our television manual analogy, the manual is responsible for pointing out never to use the television in wet conditions or plug the television into an unsuitable power source. Limits improve a customer’s expectation of what a product does and doesn’t do.

Irrespective of the business model, there are limitations. In a tech startup, there are limits to the performance of the product and what the service staff can perform. Every product, no matter how perfect, has limits. It is important to name limits in the early game and avoid friction which can eventuate later when the customer’s expectations are not met.

Price is a limit, especially when the product is not free or offers no free trial. Along with the price, the product fact sheet can track other limits like the number of units sold in each pack. Not every product is available 24/7. For example, a hair salon offering hair styling services may only be available from the hours of nine in the morning till five in the afternoon. Limits are experienced in a restaurant business, a consulting firm, and internet startups.

Restaurants serve what is on the menu. They have the ingredients readily available to create a set of dishes. Making limits known early manages customer expectations and reduces the chance you will inconvenience a customer. Placing trading times on Google Maps tells customers when you are open before they leave their homes. Offering a menu when a customer arrives tells the customer what is available.

If you have ever been told your credit card is not accepted when trying to pay the bill, it is likely the restaurant didn’t make limits known in the early game.

Remember: a customer learns as much from the list of functions as they do from the list of limits. The boundaries of expectations are defined by both.

q. Are you mapping workarounds in Q2?

There are times when customer support can prescribe a work-around. Work-arounds are a temporary measure designed to overcome friction until a more satisfactory result can be achieved. They permit a sale, without future-sell.

Even technology giants like Google with above USD 1BN market cap solve product limits with work-arounds. Below is a real-life example of how Google uses a work-around to answer a customer’s query about customizing a Google Doc:

Here are four Quadrant 1-2 fits 🕹 which name limits and work- arounds.

q. Are you guarding customers from future-sell?

Future selling is when someone in the startup commits the company to build a feature tomorrow, in order to make a sale today. The startup falls foul of making the sale contingent on a feature that may not have been specified, costed or thoroughly tested with the code-base. Because the feature is unspecified, the precise date of the release is hard to predict, making the sale a moving target.

It is easy to confuse the company vision with the product, thereby future selling. The sale is the truth; it is where the rubber meets the road. Performing both can see visionary messages mix with sales messages, such that staff and customers think the product of the future is here now.

For this reason, many founders now include a “forward-looking statement” to try to indemnify them from accusations of future-sell.

I consulted to a startup where we future sold so often, the lines between what was fact and fiction became blurred. Each person in the company sold a different version of the product. Future sell to enough customers and your entire product roadmap is railroaded. You spend your days reporting to each customer on progress towards a future sale. With so many promises competing for resources, the company fails to deliver to all customers and you close no deals. No happy customers, no roadmap – just a big mess.

To protect buyers, some countries like Australia have outlawed the practice of future-sell. If you decide to sell a financial product, you are not permitted to talk about the product until it is launched.

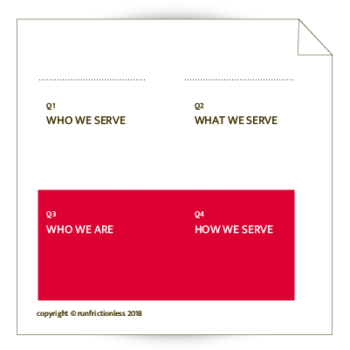

q. Are you forcing your organization to operationalize every value from Q3 in Q4?

Once you have a belief, you can figure out your values. Values drive-home the belief and make sure the belief is shared. Values help operationalize a belief and make the belief easy to apply to everyday situations.

Now, that doesn’t mean you draft a dozen values. In truth, you can probably afford to only operationalize two or three values. Here’s why.

Firstly, include only values that return value to a profile in Quadrant 1. Remember, we don’t serve everyone and therefore, we don’t need to empathize with everyone.

Secondly, for each value you espouse, you need one interaction from Quadrant 4 to demonstrate that specific value. The company must be prepared to invest dollars. Without an investment in Quadrant 4, organizations have vanity values.

Vanity values add friction because they are not actioned. They take up precious space where other words and pictures could appear. Worse, organizations with vanity values are deceiving their staff, shareholders and customers. An example of this deception is the story of the CEO who wanted his retail business to become agile. This CEO recently learned how companies were becoming agile. He became convinced if other companies were agile, his business needed to be agile.

The CEO spent the next six months convincing prospects and customers his organization was agile. While people outside the business believed him, the CEO did not spend time discussing this value inside the organization.

Here are a few problems that ensued.

Firstly, the organization did not reward staff for transforming Quadrant 4. Rather, it penalized them. If your idea failed, you failed with it. Secondly, while the CEO made a big splash outside the company, he spent no time sharing his value inside the company. Staff found it difficult to connect how agile translated to a benefit to customers, and as such, largely ignored it.

Later when customers contacted the organization, they discovered nothing had changed. Piercing the organization’s marketing veneer, customers found themselves face-to-face with the same processes and cultures from before. They had been served a vanity value and had been deceived.

get started

using the

4Qs

4Qs SLIDESHARE RESOURCES

OTHER FREE RESOURCES

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Marcus Cauchi is an outspoken critic of what’s broken in sales today. Founder of Clientology, he teaches sellers how buyers buy so the selling takes care of itself. A champion of #BuyerSafety, #PartnerSafety and #SellerSafety, he helps managers evolve into their role to get the very best out of their salespeople. Founder of Sales: A Force For Good, podcaster and facilitator of The Black Pearl strategic alliances mastermind.

run frictionless

now for only US$995